Get our latest book recommendations, author news, competitions, offers, and other information right to your inbox.

The Ancestral Power of Amulets, Talismans, and Mascots

Folk Magic in Witchcraft and Religion

Table of Contents

About The Book

• Looks at the age-old spiritual principles, folklore, and esoteric traditions behind the creation of magical objects as well as the use of numbers, colors, sigils, geometric emblems, knots, crosses, pentagrams, and other symbols

• Explores hundreds of artifacts, such as hagstones, Norse directional amulets, car hood mascots, objects made from bones and teeth, those connected with plants and animals, charms associated with gambling, and religious relics

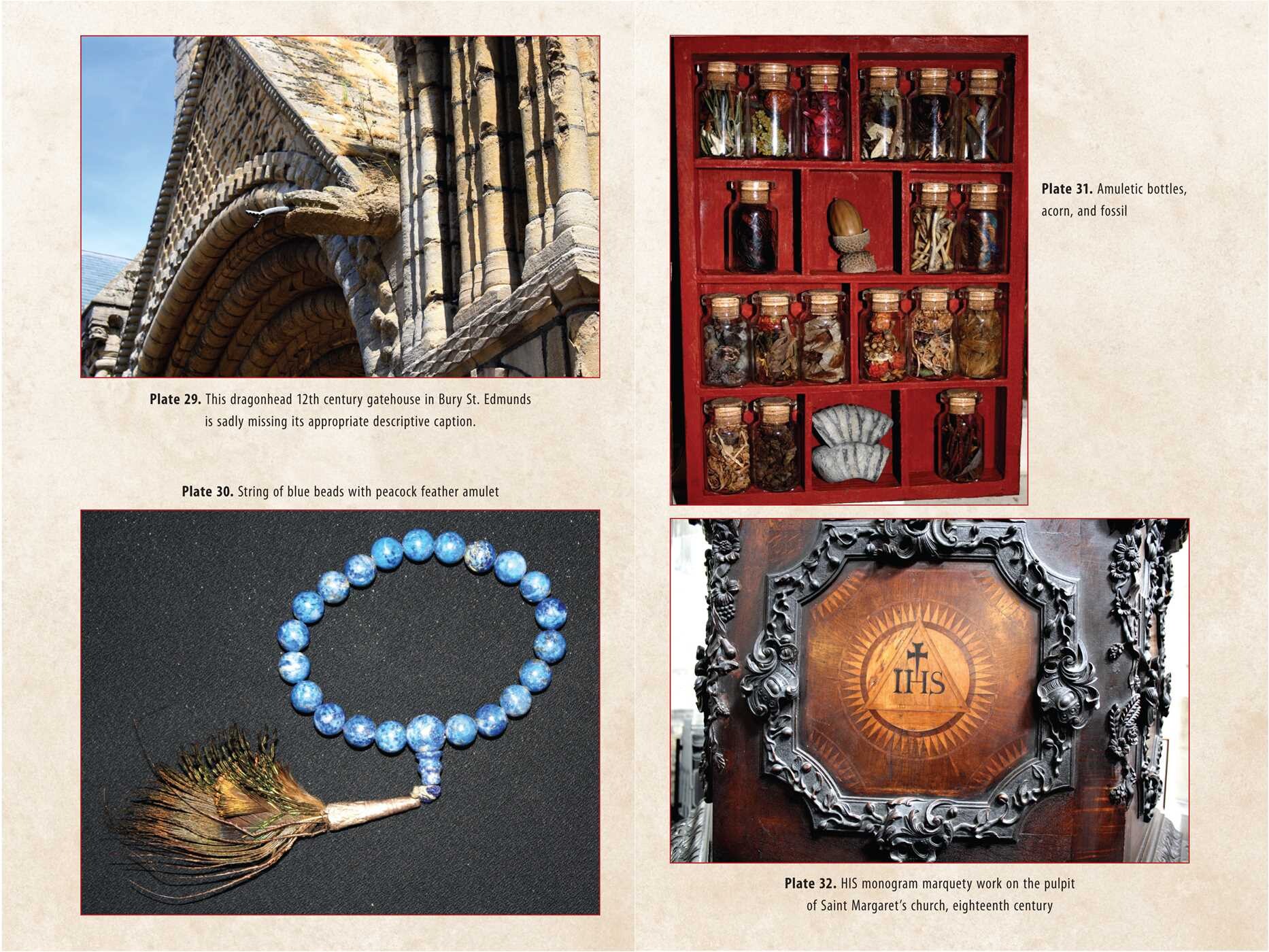

• Includes photos of artifacts from the author’s extensive collection

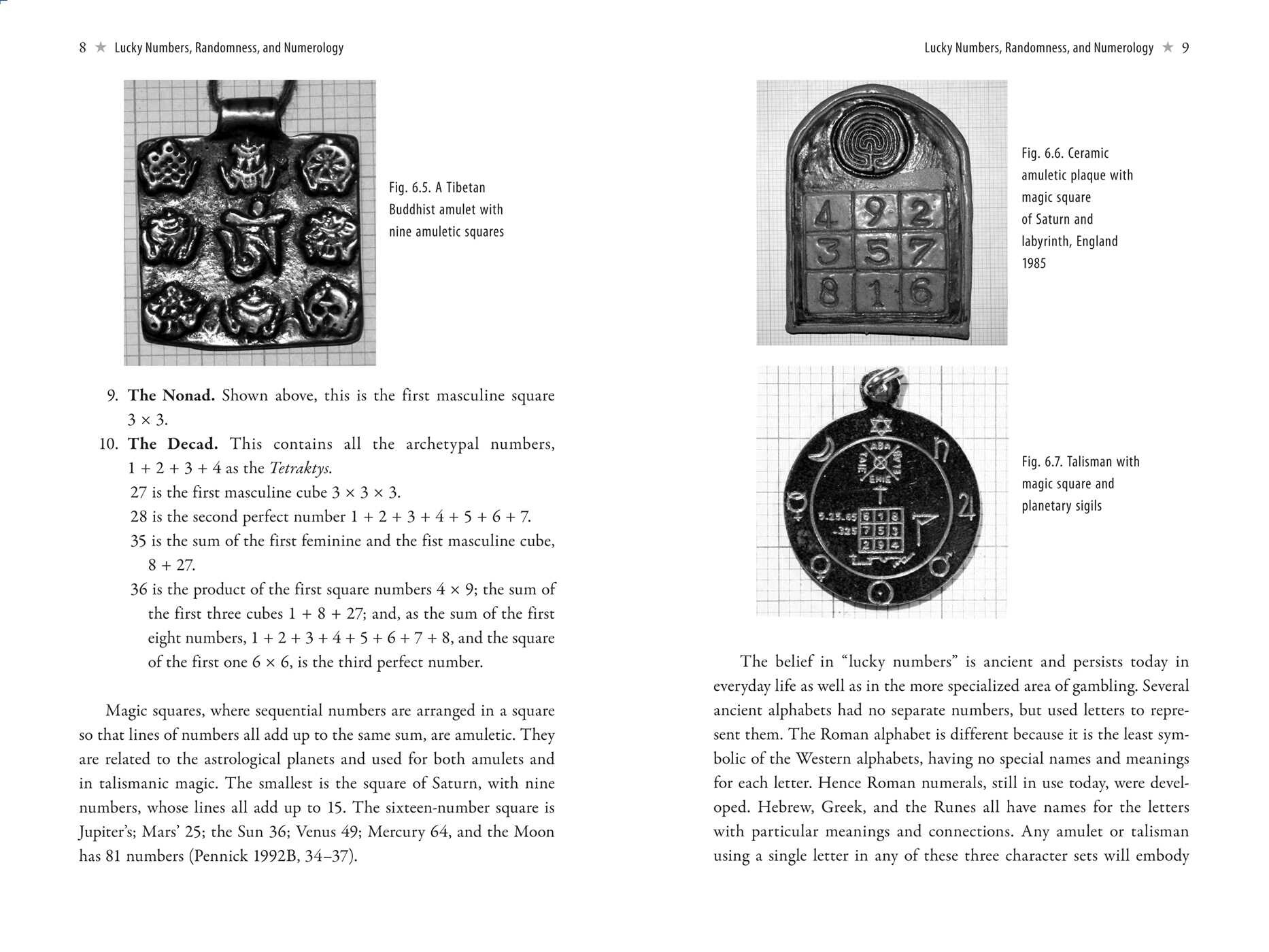

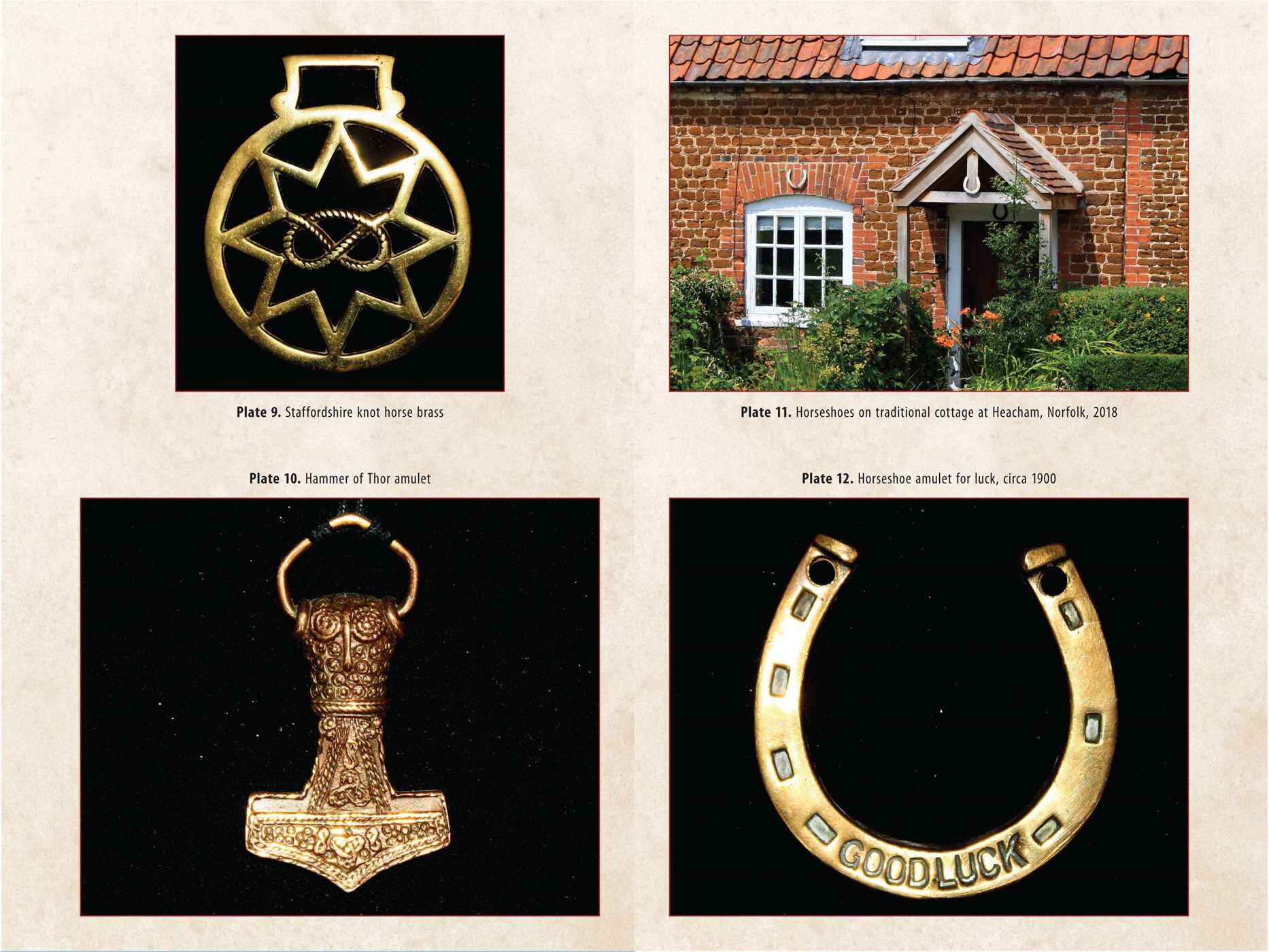

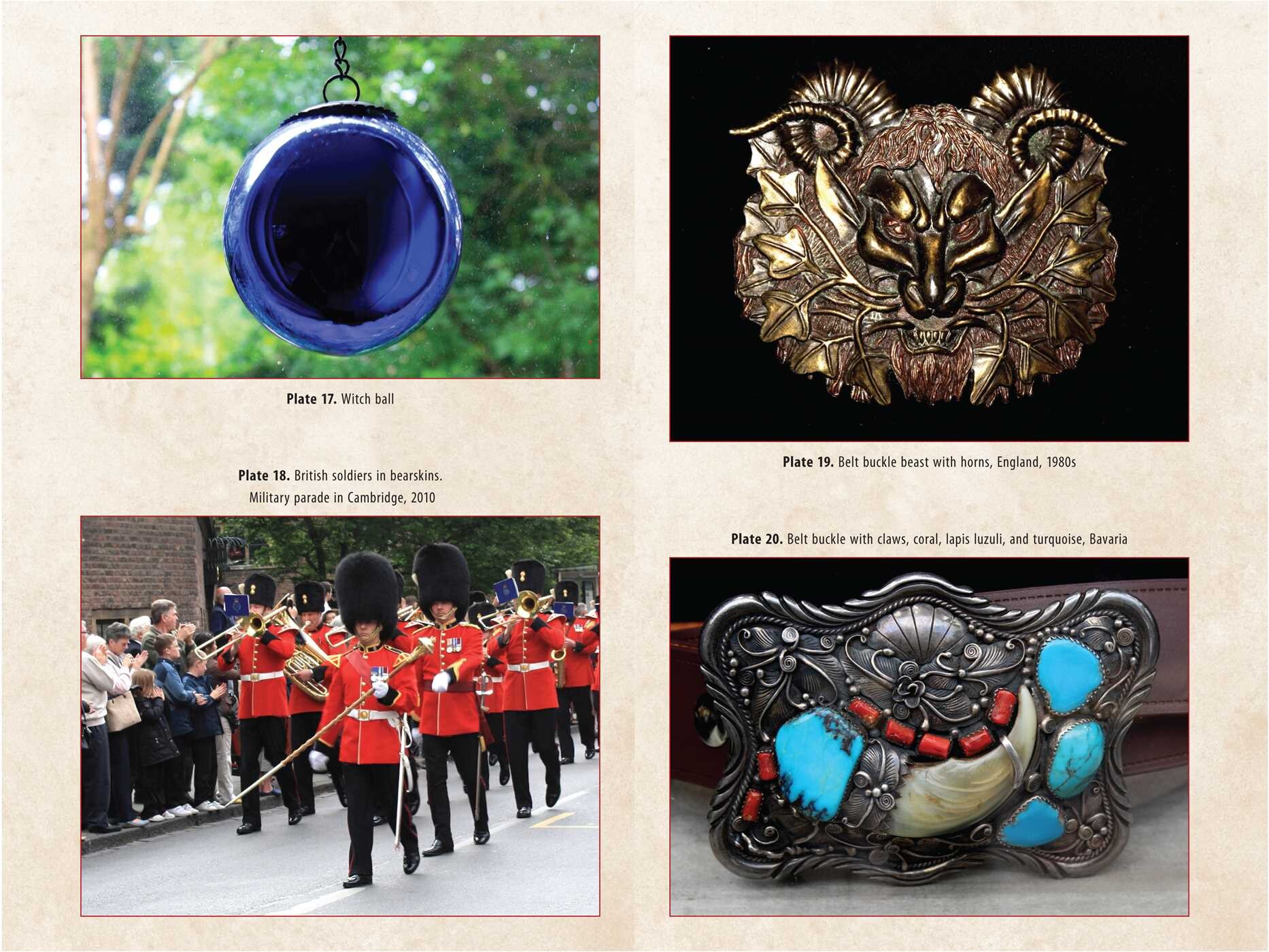

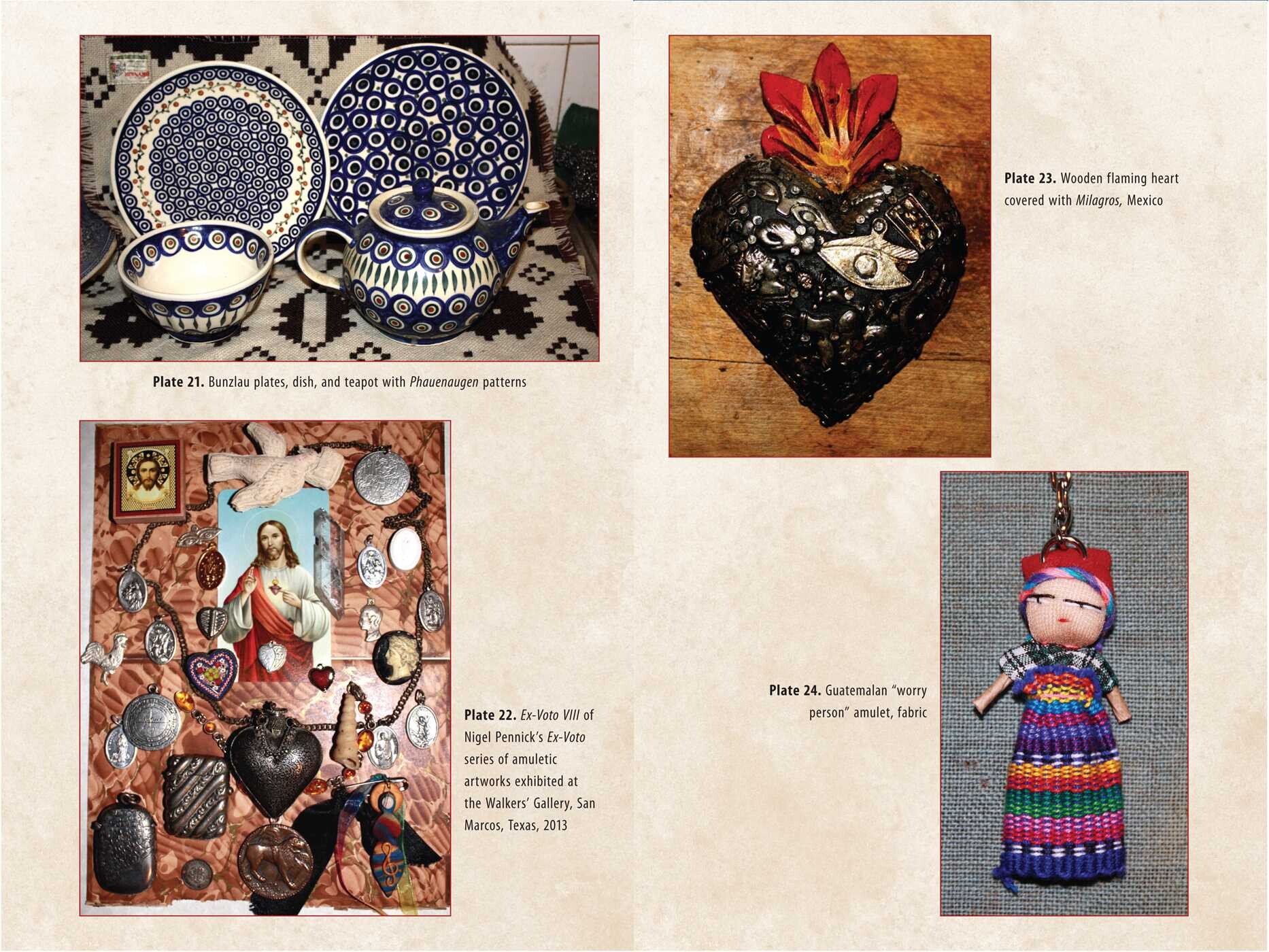

Offering an illustrated exploration of the origins and history of amulets, lucky charms, talismans, and mascots, including photos of unique and original artifacts from his extensive collection, Nigel Pennick examines these objects from a magical perspective, from ancient Egypt to the present. He looks at the age-old spiritual principles, folklore, and esoteric traditions behind their creation as well as the use of numbers, colors, sigils, geometric emblems, knots, crosses, pentagrams, and other symbols.

Pennick explores magical charms and objects manufactured from bones, teeth, claws, and horns and those that include symbols of the human body. He also discusses religious relics as well as the combining of charms to make more powerful objects, from the bind runes of the Norse and the crowns of ancient Egypt to the Mojo hand and the medicine pouch.

Revealing the lasting power of amulets, talismans, charms, and mascots, Pennick shows that these objects and symbols have retained their magic across the centuries.

Excerpt

Things worn around the neck as pendants or carried somewhere on the person are generally amulets. As C. J. S. Thompson characterized them: “the belief that certain objects, natural or artificial, composed of metals, stone, clay, or other materials sometimes possess occult powers capable of protecting those who carry them from danger, disease, or evil influences” (Thompson 1932, 229). Often, collections of amulets and talismans are worn together, as on “charm bracelets.” They may include beads, objects of stone, coral, amber, silver, and gold, and the claws of eagles and bears, wolves’ teeth, toads’ bones, and snake vertebrae. Teeth, claws, and bones link the wearer to the corresponding animal powers. In traditional societies, animal powers are incorporated into personal identity. The úlfheðnar and berserkir of Viking times were warriors who drew on the power of the wolf and the bear, respectively, and in later medieval times, kings such as Heinrich der Löwe (Henry the Lion) of Saxony, Richard Coeur de Lion (Lionheart) of England, and Henry the Lion of Scotland drew on the power of the lion for their fighting prowess.

Charms are amulets that have the power to hold the unknown at bay. They serve as protection against unknown and unprecedented events. Elizabeth Villiers, writing in 1923, described the universal attraction of luck-bringing charms:

“The airman carries his luck bringer in his “bus” when he attempts his greatest flights; the motorist has a mascot on his car. Tennis players, even the most celebrated champions, go to the courts thus protected, so boxers enter the ring. Cricketers and footballers go to the ground with their mascots, while the thousands of spectators who watch the matches carry the chosen luck-bringers of their favourites, hoping to give them victory. In racing it is the same, and it is well known that gamblers have the greatest belief in luck bringers. . . . The lover places his ring--a mascot--on his sweetheart’s finger; the bride goes to the altar carrying her mascot of white flowers; the mother buys her baby the coral and bells, which are the mascots of childhood. The businessman has a paper-weight on his desk, and its shape is that of a horseshoe or a stag or an elephant--all-important mascots to bring commercial success. Recently an explorer set sail after having been presented with so many mascots by admirers that he was obliged to leave most of them behind, while a man tried for his life at the Old Bailey, stood in the dock with a row of mascots behind him.” (Villiers 1923, 9-10)

Villiers defined the spiritual rules that govern the use of luck-bringers. She asserted that only a charm that had been given as a gift to the owner could be effective. If one bought one for one’s own use or obtained it unjustly, then its power would be ineffective. Furthermore, if one is an unworthy person, it will not bring good fortune (Villiers 1923, 1).

Mascots are said to be most powerful if they are worn on the left side (Villiers 1923, 1). The meaning of the word mascot has altered since Villiers’s time. Mascot originated in France around 1867, with a general meaning of a lucky charm, an amulet, or talisman. Popularized by Edmond Audran in his opera La Mascotte (1880), it was absorbed into English with the same meaning. Subsequently, the meaning of the word has become restricted to a lucky image, often a person in costume who functions as a cheerleader at sporting events. From the 1970s, the rock bands the Grateful Dead and Iron Maiden have had skeletal images as their logos, mascots called Skeleton Sam and Eddie, respectively.

Places of Spirit

In pre-Christian Europe ancestral holy places--homesteads, grave mounds, tombs, and battlefields--were venerated as dwelling places of ancestral spirits, which were not seen as necessarily malevolent. Sagas, legends, and folktales recounted notable events that occurred there, which explained the meaning of their names. Gods, heroes, spirits, demons, events of death and destruction, apparitions, and accidents are recalled in place-names and their associated stories. Some remain today, places where people can experience transcendent states of timeless consciousness, receive spiritual inspiration, and accept healing. Materials from such places, such as dust scraped from standing stones, were (and are) considered somehow to contain some of the power.

It is possible to carry away the inherent magical properties of materials from specific places deemed sacred. Twigs, cones, fruit, seeds, and fragments of wood from holy trees can be made into amulets, either unaltered or by transformation into images. Likewise, pieces of stone chipped from sacred megaliths or other images contain the sacred power.

For thousands of years, small sacred images and talismans have been sold at places of pilgrimage to be taken back home by pilgrims as a token that they have been there and also as powerful objects in their own right. Tourists’ souvenirs are a secular continuation of these relics of pilgrimage. This is what André Malraux called the persisting life of certain forms reemerging again and again like specters from the past (Malraux 1978, 13). Dust from standing stones and graveyards, pieces of sacred trees, wood from trees in Nazareth and Jerusalem or the British Royal Oak, Irish stones, or water from the River Jordan, the Zamzam Well at Mecca, Holywell, or Walsingham are all instances of this. Grave dirt, imbued with the essence of the dead, is an important ingredient in certain powders used by practitioners of hoodoo.

Product Details

- Publisher: Destiny Books (June 10, 2021)

- Length: 352 pages

- ISBN13: 9781644112205

Browse Related Books

Raves and Reviews

“This is a very well-researched and well-written book, presenting great information through many photos of artifacts with annotations to help decode the meaning of the signs, numbers, and symbols used in witchcraft practices and esoteric traditions in general. It certainly is an inspirational work, and it sparks your interest in other topics. This book gives what is surely the most authoritative account of symbolism and practices in witchcraft available.”

– Natasha Helvin, author of Slavic Witchcraft

“Written by one of the great wisdom keepers of British lore, this book is the most wonderful treasury of amulets, protective emblems, and the folklore by which people have kept themselves safe against plagues, envy, and evils of many kinds. Very highly recommended as an authentic sourcebook of protective wisdom.”

– Caitlín Matthews, coauthor of The Lost Book of the Grail

“The wise words of Nigel Pennick are amplified by the feast for the eyes in the images cataloging the ability of human beings to imbue power into objects as well as the innate ‘manna’ contained in certain shapes, words, and symbols. I am grateful for Nigel’s valuable insights in this historical, multicultural, spiritual archive of fetishes and how they empower individuals in the face of authoritarian oppressive decrees. If you thought you knew everything about sigils, seals, talismans, and symbols, get ready to expand--thanks to Nigel’s masterful scholarly work contained within these pages.”

– Maja D’Aoust, author of Familiars in Witchcraft

“This substantial compendium, documenting amulets and talismans’ myriad manifestations, is pure Pennick and sans pareil. It is not only based upon a lifetime of learning but also the author’s own artistic craftsmanship and keen-eyed collecting, as evidenced by the wealth of accompanying images. The result is a gem-studded wizard’s chest of living folklore, overflowing with contents that cannot fail to fascinate and enchant.”

– Michael Moynihan, Ph.D., coauthor of Lords of Chaos

“The breadth and depth of Pennick’s knowledge of folklore and magic never fails to deliver, and his latest work is no exception. Reaching across multiple cultures and spanning time from ancient history into the modern era, this book covers all aspects of the magic that deals with created objects and symbols of all varieties. The creation of amulets, talismans, and charms is the meeting of the numinous and the practical, embodying the desire and vision of the maker into a manifested creation, and this book covers all aspects of this most practical form of magic. Accompanied by numerous illustrations, this would be a welcome addition to any collection.”

– Alice Karlsdóttir, author of Norse Goddess Magic

“This book will inspire the reader to create sacred and magical objects, using media such as knotwork, ropes, bells, feathers, roots, bones, stones, and herbs. Numbers, colors, glyphs, and signs are offered as suggestions to add potency to these creations. Artists, magicians, witches, and Druids who seek to create physical objects of power and protection will find herein a treasure trove of historically grounded practices.”

– Ellen Evert Hopman, author of The Sacred Herbs of Samhain

“What we have in Pennick is a modern-day cunning man. He is not only an authority in the field of folk magic but an active magical practitioner who is in tune with the energies and rhythms of landscape, symbol, and the timeless rituals and traditions that have helped to bolster man’s connection to a universe that is alive. Ancestral Power of Amulets, Talismans, and Mascots is a boon to students of folklore and practitioners alike.”

– Johnny Decker Miller, author of Dark Magic

"Nicely illustrated throughout, The Ancestral Power of Amulets, Talismans, and Mascots: Folk Magic in Witchcraft and Religion is an amazingly informative compendium and must be considered an essential, core addition to personal, professional, community, college and university library Metaphysical Studies collections in general, and Rune Divination, Witchcraft, Ancestral Religion, and Folk Magic supplemental studies curriculum lists in particular."

– Midwest Book Review,

“The Ancestral Power of Amulets, Talismans, and Mascots opened my eyes to all the ways people of different cultures and eras created and utilized amulets, charms, and mascots. As always, religion played a heavy hand in their evolution, but so has community tradition. Pennick has an impressive personal collection of these items and thankfully shared much of it as photos in the book. So many wonderful photos and illustrations! I’m not going to say that The Ancestral Power of Amulets, Talismans, and Mascots by Nigel Pennick is for everyone, but if you ever found yourself curious about some of the symbols you see people wearing or adorning their homes with, this is absolutely the perfect book for you."

– The Magical Buffet

"Nigel Pennick is described by Caitlín Matthews, “one of the great wisdom keepers of British lore”. A description with which I would agree; the depth of his knowledge is astounding and his books are peerless in the way they present authentic explorations of this particular field, making compelling and very accessible reading."

– June Kent, Indie Shaman magazine

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): The Ancestral Power of Amulets, Talismans, and Mascots Trade Paperback 9781644112205